As drug discovery methods develop, and the complexity of the molecules grows, so too must the means of delivery.

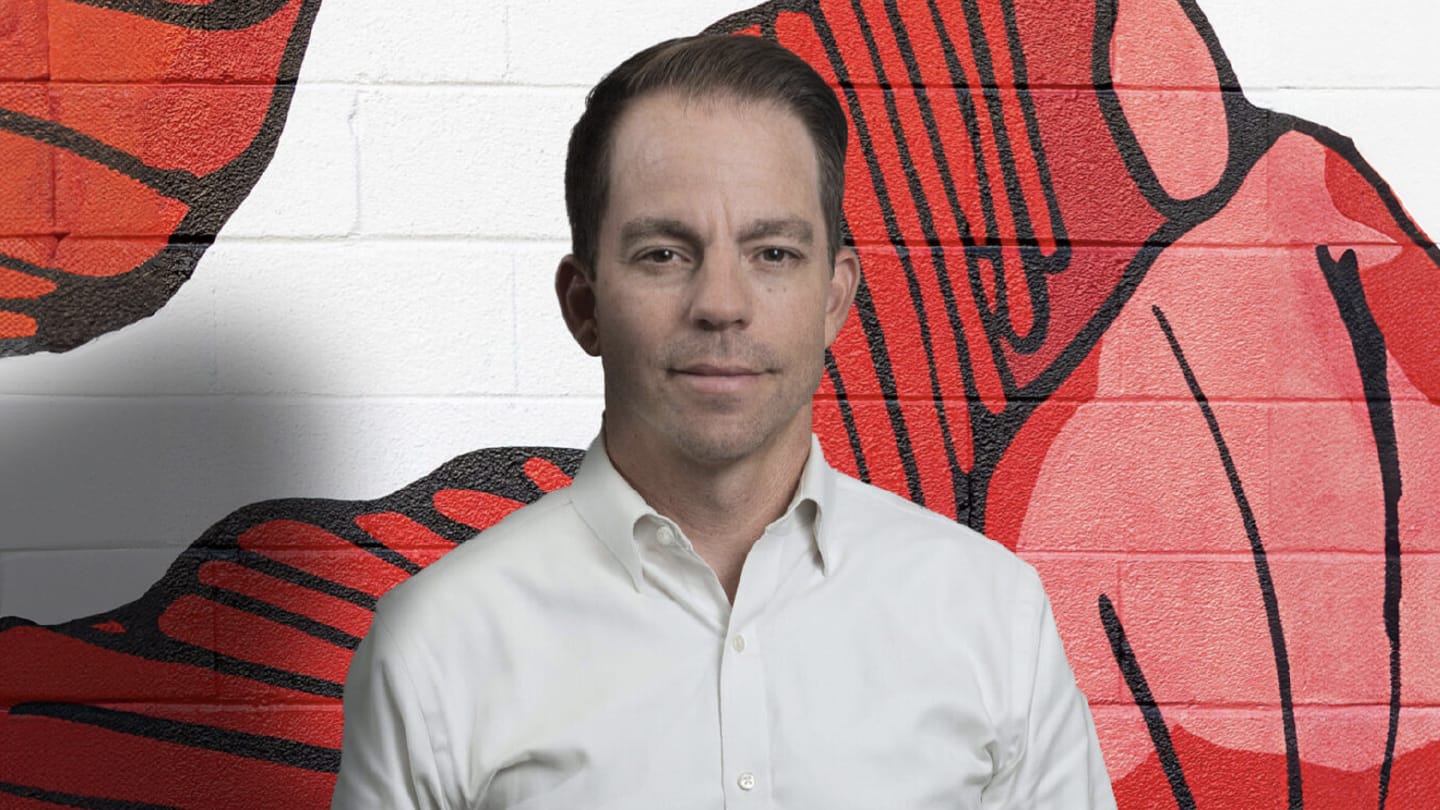

Drug discovery and delivery was once a simple process: pound a plant with a pestle, ingest, and await the effects. When this process found its way into the lab, the discovery of more and more compounds meant more and more complexity. Hence the arrival of drug delivery technologies from spray drying to LNPs. Now, in the age of omics, in silico discovery methods are making a myriad of compounds available, but they all share one thing in common: they are so much more difficult to absorb. CEO Elizabeth Hickman and CSO Dave Miller of Austin Px explain how delivery technology is continuing to evolve to keep up.

The percentage of poorly soluble drugs in company pipelines continues to grow. What do you think is driving this increase?

Elizabeth Hickman: All the easy molecules have been discovered, but what's really driving it is new technologies like structure-based drug design and AI have opened up the “undruggable” targets and proteins that were otherwise considered unreachable. These molecules usually have more challenging structures; they break Lipinski’s rule of five, which makes them more difficult to develop. Although they are becoming more challenging, development scientists are keeping up with them by creating the technologies that can keep up.

One of those technologies is Austin Px’s KinetiSol, of which Dave is a co-inventor. Can you elaborate?

Dave Miller: When humans began discovering drugs, it was done irrationally. The library was nature. Certain plants and other natural materials became known for certain pharmacological effects, but there was no concept of how those compounds work in the body.

In the early days of modern chemistry, those active molecules were extracted from the source, identified, and modified. It was not until the late 20th century, through genomics and proteomics, that we started to understand disease pathways, target sites, and how small molecules interact to elicit a therapeutic effect. Now we can screen molecules against those target sites to find one that binds to provide the therapeutic effect. The library shifted from nature to the laboratory using combinatorial chemistry to create things that hadn't existed in nature.

Compounds were getting bigger and more lipophilic. As a result, solubility decreases. The conventional tools of drug delivery couldn't accommodate these molecules – hence the onset of super saturating delivery systems like lipids, self emulsifying drug delivery systems, hot melt extrusion, spray drying, and nanoparticles as ways of delivering insoluble molecules.

Now, in what I call almost the second phase of rational discovery, in silico, computer-assisted machine learning means these molecules don't have to be synthesized to screen them against the target site. We're producing libraries of compounds in cyberspace, so molecules are trending more and more toward being difficult to deliver. The old tools – lipids, nanoparticles, spray drying, hot melt extrusion – are no longer giving full coverage. So out of that necessity is born new inventions in the drug delivery space. That's where KinetiSol was born. KinetiSol eliminates a lot of the limitations and offers a path forward for these very difficult molecules.

Why do poorly soluble drugs remain so difficult to deal with?

DM: A lot of the solubility issues we deal with stem from two main factors: the molecular structure and lipophilicity of the compound, and the crystal habit, which is the stability of the drug in its crystalline form. To absorb a drug, we need to convert that crystal into free, individual drug molecules that can dissolve. The crystal structure itself is one of the biggest barriers to dissolution and, in turn, absorption.

Spray drying and melt extrusion were developed to overcome this using organic solvents or heat respectively. Heat was generally preferred early on, since avoiding organic solvents in medicine manufacturing is always desirable. The concept was simple: take a crystalline drug, convert it to its molecular form, and then prevent it from recrystallizing by mixing it with another material – typically a polymer. By co-melting the drug and the excipient, then solidifying the mixture, you get a solid solution, which – once ingested – would quickly convert to a liquid solution, making the drug more readily absorbed.

In the early days, that worked well because many drug molecules were relatively heat-stable and had low melting points, but as drug molecules became more structurally complex, they became more heat-sensitive, with higher melting points. When you approached the melting point of the drug, you risked degrading it or the excipient. As a result, melt processing fell out of favor and solvent-based processing became the standard.

However, many newer compounds are not only insoluble in water but in most organic solvents. That makes solvent processing increasingly difficult. Because of these challenges, many promising molecules hit a dead end. They may bind beautifully to their biological target, but once synthesized as a solid drug substance, they prove nearly impossible to dissolve or melt for formulation.

That’s the gap KinetiSol was created to address. The process doesn’t rely on organic solvents but uses mechanical energy, with only brief exposure to heat. This allows us to process drugs without depending on their melting temperature, while drastically reducing the risk of thermal degradation. Unlike conventional thermal methods that take minutes, KinetiSol operates on the scale of seconds.

EH: When you look at amorphous dispersion technologies, they have the ability to solve problems that need to be solved. We have life changing, life saving technologies coming out of discovery, but there remains the need to get them into human form. These technologies have evolved and adapted to what needed to be done, but they've also brought with them manufacturing challenges. Commercial scale manufacturing using spray drying alone, for example, can be very complex. With the lower solubility, spray times are increasing and, as a result, so are the costs and potential risks to the manufacturing of these drugs – the environmental footprint of using metric tons of solvent notwithstanding.

With in silico discovery tools and new delivery tools, we can now target pathways that were previously thought undruggable. With those pathways came new drugs for persistent, chronic diseases, and more options to treat more varieties of disease. Oncology in particular involves a lot of insoluble molecules because they're targeting disease pathways that have not been targeted before for various reasons. Now they are available.